MIPS Basics and Procedures

MIPS Basic Codes

MIPS code for if statements

- If the condition is an equality use beq, bne

- If the condition is a comparison combine beq/ bne with set-on-less-than

Why not blt or bge? While blt and bge (pseudo-instructions) are available in MIPS, beq and bne are favoured inconditional statements for their efficiency making them the common choice.

Example 1) Given,f:$s0, g:$s1, h:$s2, i:$s3, j:$s4

if(i==j)

f = g + h;

else

f = g - h;Solution 1 :- Corresponding MIPS code

bne $s3, $s4, else

add $s0, $s1, $s2

j endif

else: sub $s0, $s1, $s2

endif: ...........Example 2) Given,f:$s0 ,g:$s1 ,h:$s2 ,i:$s3 ,j:$s4

if(i<j)

f=g+h;

else

f=g-h;Solution 2 :- Corresponding MIPS code

slt $to, $s3, $s4

beq $to, $zero, else

add $s0, $s1, $s2

j endif

else:

sub $s0, $s1, $s2

endif: .......MIPS code for Loop statements

Although there are said to be 3 different types of loops in C namely, do/while, while and for loop, they are all functionally identical. In other words, you can take any for-loop and easily turn it into a while-loop.

int i;

for(i= 0 ;i< 10 ;i++){

loopbody;

}or

inti=0;

while(i< 10 ){

loopbody;

i++;

}Example 1) Given, i:$s3, k:$s

while(i < j)

i+=1;Solution 1 :- Corresponding MIPS code

loop:

slt $t0, $s3, $s4

beq $t0, $zero, exit

addi $s3, $s3, 1

j loop

exit: ...Example 2) Given i:$t0, k is some integer

int i;

for(i = 0; i < k; i++){

// loop body

}Solution 2 :- Corresponding MIPS code

add $t0, $zero, $zero # i is initialized to 0, $t0 = 0

Loop: // loop body

addi $t0, $t0, 1 # i ++

slti $t1, $t0, 4 # $t1 = 1 if i < 4

bne $t1, $zero, Loop # go to Loop if i < 4Example 3) Given, i:$s3, base address of arr:$s6, k:$s

while(arr[i] == k)

i+=3;Solution 3 :- Corresponding MIPS code

loop:

sll $t0, $s3, 3

add $t1, $t0, $s6

lw $t2, 0($t1)

bne $t2, $s5, exit

addi $s3, $s3, 1

j loop

exit:...Procedures in MIPS

Understanding the memory layout and the way procedures are called is crucial for writing efficient and correct MIPS assembly code.

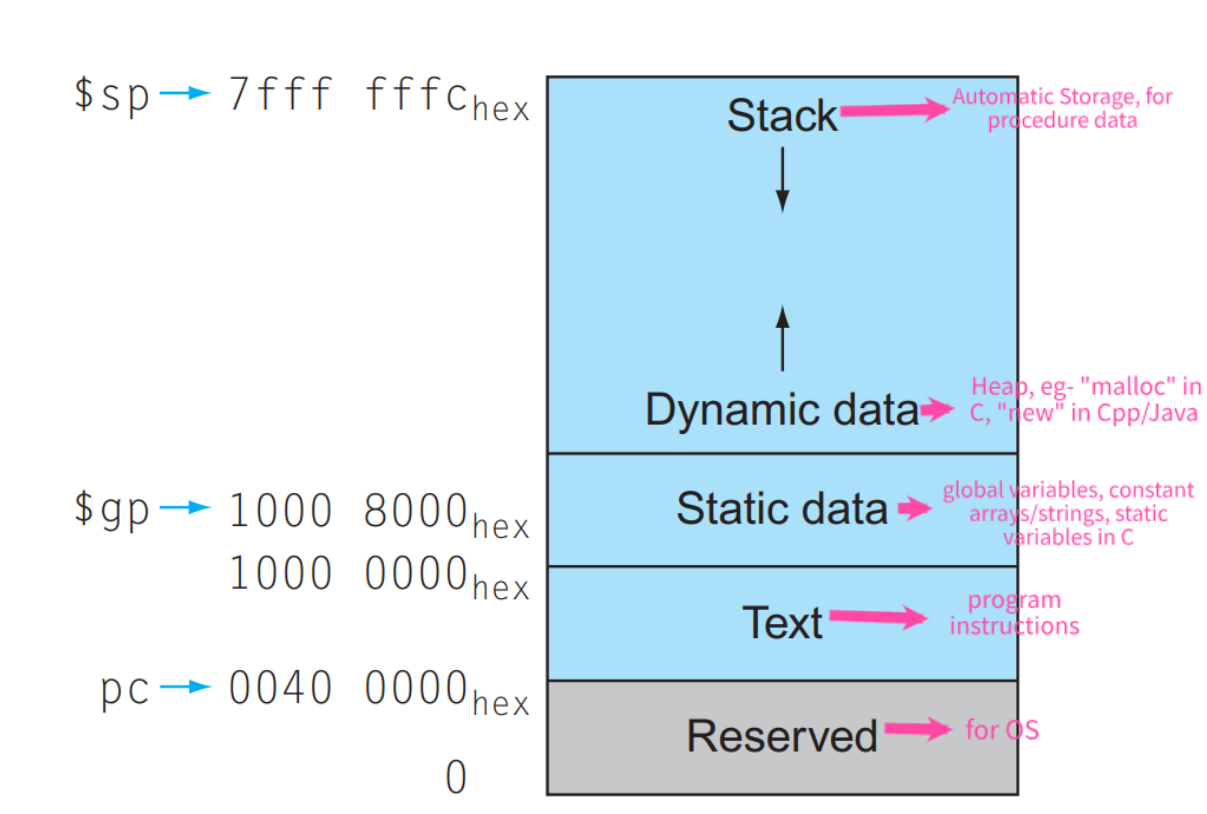

➢ Memory Layout

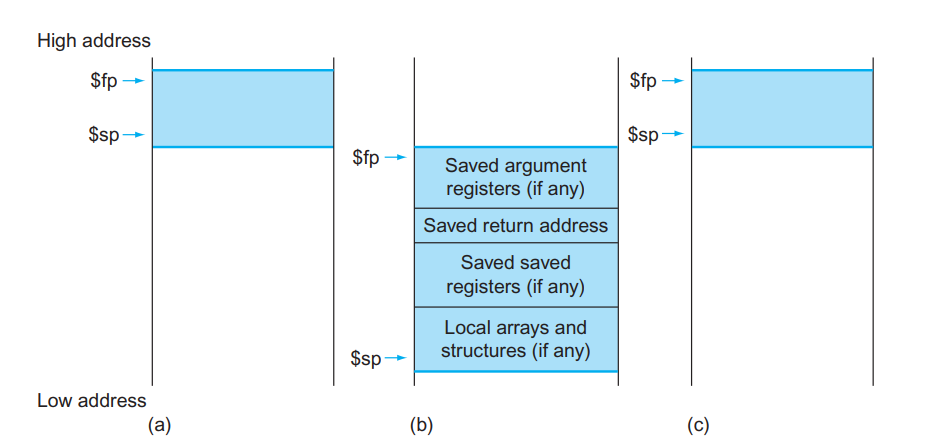

➢ Stack allocation (refer Recursion in MIPS(non-leaf procedure) for detailed explanation)

(a) before, (b) during, and (c) after a procedure call.

There are two types of procedure calling-

1) Leaf Procedures: These procedures do not call other procedures.

When a leaf procedure is called:

● There turn address is saved on the stack. ● A stack frame/procedure frame/activation record is setup to store local variables. ● Arguments may be passed in registers or on the stack. ● The procedure executes its code.

Upon completion,it restores the stack pointer and returns to the saved return address.

2) Non-leaf Procedures(NestedProcedures): These procedures call other procedures, eg.- Recursive Functions/Procedures.

In addition to the steps for leaf procedures, non-leaf procedures must manage:

● Saving and restoring additional registers beyond there turn address. ● Managing multiple levels of procedure calls and returns. ● Ensuring that data in registers is preserved a cross nested calls. ● Properly handling there turn value from called procedures.

★ Function (Procedure) calling in MIPS

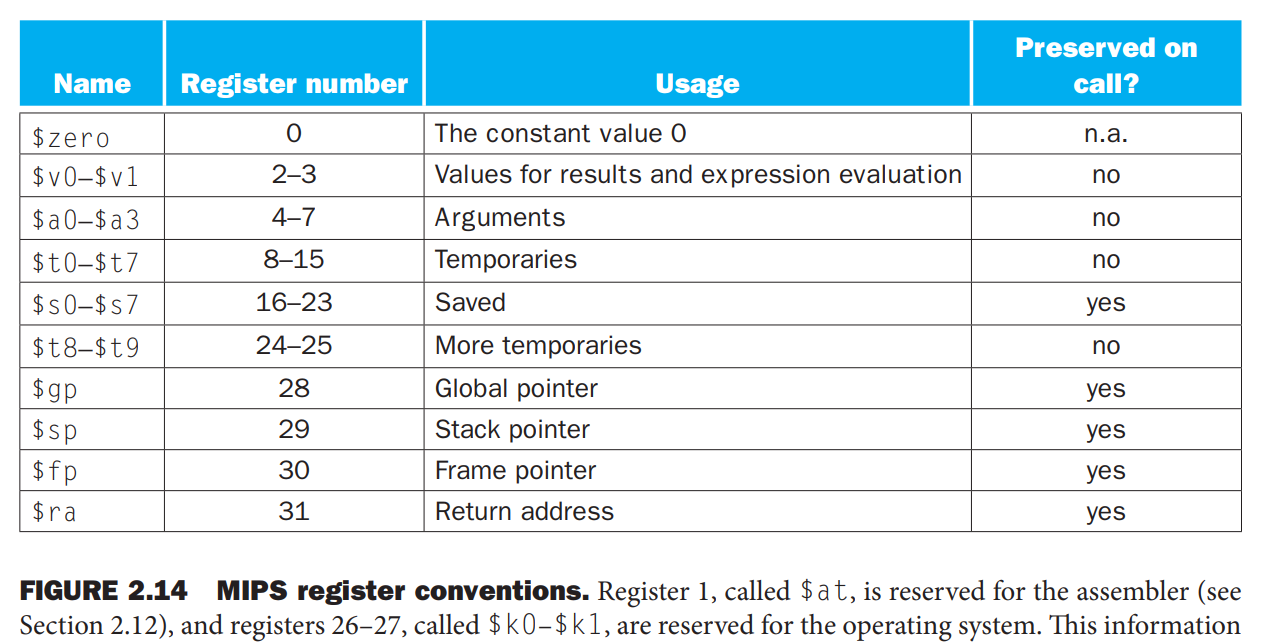

In MIPS assembly language, passing parameters to functions involves using registers. Unlike high-level languages where parameters are often passed on the stack,MIPS typically uses specific registers for passing arguments.

● $a0 to $a3 :These are argument registers and are used to pass the first four arguments to a function. If a function has more than four parameters,additional parameters are typically passed on the stack.

● $v0 and $v1: These are value registers and are used to return values from functions. Functions can return up to two values using these registers.

(Note:-i) Register 1, called $at, is reserved for the assembler.

ii) Registers 26–27, called $k0–$k1 are reserved for the operating system.)

➢ Steps in calling a procedure (function)

In MIPS assembly language, procedure calling follows a similar structure to function calls in high-level languages like C.

The following steps typically occur in both leaf and non-leaf functions but there are some nuances in how they're implemented, especially regarding the handling of the stack:

● Arguments Passing :.Arguments to the function can be passed via registers or the stack, depending on the calling convention. In register-based passing, arguments are loaded in to designated argument registers like $a0-$a3. If there are more arguments than available registers, excess arguments are typically passed on the stack.

● Jump and Link (jal) :jal makes the control jump to the given address while storing there turn address at PC+4 in the $ra register This effectively sets up the return mechanism for the function call.

● Function Prologue (Non-leaf functions): Non-leaf functions need to setup a stack frame. This involves: Saving the return address($ra) on to the stack, saving any callee- saved registers on to the stack(these are typically $s0-$s7),setting up the frame pointer($fp) to establish a reference point for accessing local variables and saved registers.

● Function Execution :The function performs its task, accessing arguments, local variables, and performing computations.

● Function Epilogue (Non-leaf functions): Before returning, non-leaf functions need to cleanup the stack frame and restore the state of callee-saved registers.This involves restoring callee-saved registers from the stack, restoring the return address($ra) from the stack resetting the stack pointer($sp) to deallocate the stack frame, jumping back to the return address using the jr $ra instruction.

● Return: Upon completing its task, the function returns control to the caller. If it's a leaf function, it typically involves jumping back to the return address stored in $ra using the jr $ra instruction. For non-leaf functions, the return sequence includes restoring the stack frame and registers before jumping back to the caller.

(Note:-For simplicity we will only use $sp and extend the stack at procedure entry/exit)

Example 1) Calling a procedure which prints a string

//code

printFunction();

a=a+2;

//codeSolution 1 :- Corresponding MIPS code

data

hello_string: .asciiz "Hello, world!\n" # String definition

.text

main:

....previous code

jal printFunction #jump to printFunction

addi $s2, 2

....further code

li $v0, 10 # Set syscall code 10 for exit

syscall # Perform syscall to exit the program

printFunction:

li $v0, 4 # Set syscall code 4 to print a string

la $a0, hello_string # Load the address of the string

syscall # Perform syscall to print

jr $ra # Return control to PC + 4● When jal is used, the control moves to the address specified in the instruction and the address of the next instruction is stored in $ra.

● When the procedure ends jr $ra is used to return control back to the next address from where it jumped.

● These procedures are usually placed after the “main” procedure to avoid instruction overlap.

Example 1) Calling a function with parameters

//code

result=addNumbers(5,7);

//codeSolution 1 :- Corresponding MIPS code

text

main:

li $a0, 5 # Load first parameter (5) into $a0

li $a1, 7 # Load second parameter (7) into $a1

jal addNumbers # Jump to addNumbers function

move $s0, $v0 # Store the result returned by addNumbers in $s0

# Further code

li $v0, 10 # Set syscall code 10 for exit

syscall # Perform syscall to exit the program

addNumbers:

add $v0, $a0, $a1 # Add the values of $a0 and $a1 and store the result in $v0

jr $ra # Return control to the next instruction after jal● In the main function, parameters are passed to the addNumbers function by loading values into registers $a0 and $a1.

● The jal instruction is used to jump to the addNumbers function.

● Inside the addNumbers function, the parameters are accessed from the $a0 and $a1 registers.

● The result of the addition is stored in register $v0, which is commonly used to return function results in MIPS.

● Finally, jr $ra is used to return control back to the instruction after the jal in the main function.

★ Recursion in MIPS (non-leaf procedure)

In MIPS assembly language, implementing recursion involves understanding function calls and stack manipulation.

The Stack in MIPS Assembly

● The stack is a crucial data structure used in MIPS assembly language for managing function calls, local variables, and return addresses. ● It operates based on the Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) principle, meaning the last item pushed onto the stack is the first item to be popped off.

Stack Operations:

Stack Pointer ($sp): ● The stack pointer register, $sp, points to the top of the stack. It keeps track of the current position in memory where new items are pushed onto or popped off the stack.

Push Operation: ● To push data onto the stack, the stack pointer is decremented to reserve space for the new item, and then the data is stored at the memory location pointed to by the stack pointer.

Pop Operation: ● To pop data off the stack,the data is retrieved from the memory location pointed to by the stack pointer, and then the stack pointer is incremented to remove the item from the stack.

Stack Usage in Function Calls:Function Prologue: ● When a function is called, the current contents of relevant registers (such as there turn address and callee-saved registers) are typically saved on the stack to ensure they are preserved. ● This process is often referred to as the function prologue.

Function Epilogue: ● Upon completion of the function, the saved values on the stack are restored to their original registers. ● This process is known as the function epilogue.

Example) Function Call and Stack Usage

● When main calls my Function using jal, the return address (the address of the instruction following the function call) is automatically saved in register $ra. ● Inside my Function, the function prologue allocates space on the stack to save the return address. ● The function body executes the desired operations. ● Finally, in the function epilogue, the return address is restored, and the stack space allocated in the prologue is deallocated before returning control to the caller.

To understand recursion in MIPS, a good understanding of the stack pointer and how it operates on memory is imperative. Recursion involves careful management of the function call stack, ensuring that return addresses and local variables are properly saved and restored. This example illustrates the process of calculating the factorial of a number using recursion in MIPS assembly language.

Example) Calculating the factorial of a number using recursion

//code

result = factorial(5);

//codeSolution 1 :- Corresponding MIPS code

text

main:

li $a0, 5 # Load the value 5 (number whose factorial is to be calculated) into $a0

jal factorial # Jump to the factorial function

move $s0, $v0 # Store the result returned by factorial in $s0

# Further code using the result stored in $s0

# ...

li $v0, 10 # Set syscall code 10 for exit

syscall # Perform syscall to exit the program

factorial:

# Function prologue

addi $sp, $sp, -4 # Allocate space on the stack for local variables

sw $ra, 0($sp) # Save the return address on the stack

# Check for base case: if n <= 1, return 1

li $t0, 1 # Load the value 1 into $t0

ble $a0, $t0, base_case # Branch to base_case if $a0 (n) <= $t0 (1)

# Recursive case: n * factorial(n - 1)

addi $a0, $a0, -1 # Decrement $a0 (n) by 1

jal factorial # Recursive call to factorial function

lw $ra, 0($sp) # Restore the return address from the stack

addi $sp, $sp, 4 # Deallocate space on the stack for local variables

mul $v0, $a0, $v0 # Multiply n by the result of factorial(n - 1)

jr $ra # Return control to the caller

base_case:

# Base case: n <= 1, return 1

li $v0, 1 # Load the value 1 into $v0

lw $ra, 0($sp) # Restore the return address from the stack

addi $sp, $sp, 4 # Deallocate space on the stack for local variables

jr $ra # Return control to the caller● In the main function, the value 5 is loaded into register $a0 to calculate its factorial.

● The factorial function is then called using the jal instruction.

● Inside the factorial function, the base case checks if the input value n is less than or equal to 1.If so,it returns 1.

● Otherwise,the function decrements n by 1 and recursively calls itself with the decremented value.

● The result of the recursive call is then multiplied by n to compute the factorial. ● Finally,the result is returned to the caller using register $v0.

References

- J.L.Hennessy and D.A.Patterson Computer Organization and Design:The Hardware/Software Interface, Fifth Edition

- “Digital Logic and Computer Design” by M.Morris Mano

- “Digital Fundamentals” by Thomas L.Flyod

- www.cs.missouristate.edu/MARS

- https://www.d.umn.edu/~gshute/mips/directives-registers.pdf

- courses.missouristate.edu/KenVollmar/mars/Help/SyscallHelp.html

- courses.missouristate.edu/KenVollmar/mars/Help/MarsHelpIntro.html

- riptutorial.com/mips/example/29993/mars-mips-simulator

- bytes.usc.edu/files/ee109/documents/MARS_Tutorial.pdf